英国经济硕士dissertation代写

1. 前言和假设:

1.1 从更广泛的角度来看这个主题:

营利性组织就是为了获取利润最大化——就是我们平时所说的“营利性”——这个概念可以追溯到非营利组织的所有者(非营利组织),营利性组织和非营利性组织之间有很大的不同,主要追求利润的与否与存在目的的差异。对于营利性组织和非营利性组织,一定要有一个明确的界限将他们分开,对于这两个组织的差异性的研究有很多,很多研究人员和专业人士对此进行过激烈的争论,这将在本文稍后讨论,这两个部门不是绝对隔离的分开的,而是边界有一些重叠的,在过去二十年左右的发展时间里,两个组织都以其独特的发展方式蓬勃发展开来。在很长的一段时间里,营利性组织也会参与志愿活动,表现出利他主义,非营利组织也会使用业务管理战略和财务管理框架进行管理和经营。然而,学者和专业人士认为,虽然非营利组织参与财务管理和货币相关的模型和框架,但最终,不同于营利组织;它不是目的,而是通往目的地的一种方式。

1. Introduction and hypothesis:

1.1 Topic a broader perspective:

For-profit organisations are meant for maximisation of profit - as it suggests when we say 'for-profit' - which goes back to the owner where as non-profit organisations (NPOs) are quite different - they are not, primarily, for profit. It suggests that there should be a basic difference which makes them stand apart. There are so many arguments by academic researchers and professionals, which are going to be discussed later in this document, in relation to both of these sectors and their boundaries by keeping in view the overlapping developments over the last two decades or so. While the for-profit organisations have been witnessed participating in voluntary activities and showing altruism, NPOs have also been observed using business management strategies and financial management frameworks for a quite long time. However, academics and professionals argue that though non-profits are involved in financial management and monetary associated models and frameworks but ultimately, unlike for-profits; it is not the end but a means to end.

End lies somewhere else which is either not yet decided - for many or rather all of the non-profit organisations - or cannot be decided in the first place (Helmut, 2000; 9).

For-profit organisations have their end products to put in display and attract customers. Their (for-profits) messages to convey about and advertise for are of utility, value, service, benefit, advantage and convenience to those who spend money. Conversely, NPOs are not supposed to do that or rather they are unable to do that. This is because they do not offer any of the above mentioned returns to actual money-spenders or donors which for-profit organisations do. They do not actually give anything tangible at all in return to whom they are collecting money from. Then what do the donors get in return of their money?#p#分页标题#e#

Here comes the main point of distinction the non-profit organisations have got a mission which can define many of these organisations objectives, or rather all of them, as remote and ethereal - i.e. empathy, compassion, sympathy, service for public good, kindness and welfare. They collect money from someone else and spend it onto someone else in need who cannot afford that much money for themselves. In this process of welfare and public good a donor gets a feeling of satisfaction, love for humanity, altruism and compassion.

Although no strict legal definition of charity exists even today and it is still in progress which makes it fairly new a sector (Helmut, 2000; 6), there seems to have a popular approach that charitable purposes can be categorised in one of four ways; the poverty alleviation; education uplift; the spread of religion; and other useful objectives for the community (Quint 1994; 1 seeHanvey and Philpot, 1996; 2)

1.2 Area of key concern:

Prior, these non-profits had been backed up and supported by state funding and they did not need to panic too much for security of revenues to keep their voluntarism for public good but as two or more decades has passed away, since 1980s, the environment for these non-profits has been rationally changed. The global economic changes and ever-increasing demand of public welfare from those NPOs have compelled this sector to adopt certain ways to sustain themselves on their own. This change has also exposed NPOs to greater financial uncertainty due to insufficient government funding and increasing expectations from society for public welfare. (Helmut, 2000; 7)

Now the time has come to focus on all of these financial issues for non-profit sector. While their responsibilities have been puffed up in the face of expanding demand for help and voluntarism now-a-days, non-profits are in dire need to devise strategies to get to their target donors in order to fulfil their mission. A key factor in the whole process of reaching their donors is marketing which is a tool normally associated with business enterprises. For instance, a simple dictionary definition of marketing shows: “the business of moving goods from the producer to the consumer”. Here goods can be taken as goods or services. The chartered Institute of Marketing UK define marketing as: “The management process responsible for identifying, anticipating and satisfying customer requirements profitably”. (Smith, 1993; 1)

So many questions and vague understanding have jumped out of the bush which make confusion about the two should-be different kind of sectors. American Marketing Association considered a need to amend definition they took profit out, possibly because it excluded a large number of professionals practising marketing on a large scale for non-profit organisations. UK perhaps favoured efficiently instead profitably or in a way that meets the organisations goals (Smith, 1993; 1-2). Keeping in view the above mentioned concepts and assumptions about for-profit organisations and non-profit organisations this thesis discusses the structural commonalities and differences between them and gradually narrows down the discussion to a key area of marketing communications.#p#分页标题#e#

1.3 IMC a preferred concept:

The Integrated Marketing Communications (IMC) concept first came forward in the 1980s and developed relatively slowly into the middle of the next decade. Smith et al. (1997) made an attempt to look at IMC from a strategic as well as a functioning perspective. Various descriptions of the term integrated include coordinated, holistic, embedded and combined. Basically, much of the underneath discussion focuses on the range of issues and whichever term is used, success is measured in terms of how effective they have been dealt with in producing measured results. The shift on emphasis from promoting to a target audience to communicating with the audience has been advocated by Hughes (1998). This has become increasingly prevalent with advances in database and media technologies. The two-way nature of communication is now in advance, even for those fast moving consumer goods (fmcg) brands with millions of globally based customers. (Tench and Yeomans, 2006; 503)

All the definitions and concepts about IMC constitute some common features and some slightly different. All these concepts about a process of building relationship between an organisation and its stakeholders can be or rather are being applied to both profit and non-profit sector. Different organisations in the light of their respective objectives and goals use IMC in a different arrangement and pattern but the key features are almost analogous. A single, common theme has much to acclaim it but it is rightly practicable to consider the integration of incongruent approaches and messages targeted at a variety of groups. What needs to be said to shareholders may well be different to messages targeted at employees, which may well be different to the trade, which may well be different to customer group A, which may well be different to customer group B. And the images accompanying these messages may also need to be different. Indeed, it may be argued that under such circumstances there is greater need for integration and management of that integration if confusion is to be avoided.

1.4 Framework for analysis:

In order to try to understand the motivational factor(s) on the part of donor(s) for a non-profit organisation, in comparison to customers of a profit organisation, this document discusses the structure and working of non-profits in general and analyses both profit and non-profit sectors, by selecting one fairly big organisation from each sector, in the light of IMC model SOSTAC in particular.

1.5 Sample selection:

In this thesis Health sector has been undertaken for analysis in both for-profit and non-profit sectors. Boots a leading pharmacy retailer in UK has been selected as a sample from for-profit health sector and on the other hand Cancer Research UK has been chosen from non-profit health sector.

1.6 Rationale:#p#分页标题#e#

This research will analyse the working and structure of for-profit and non-profit sectors in the light of concepts and definitions discussed by a numerous academics and professionals. More specifically, it will attempt to explore the organisational structure, their objectives and key features of importance in both sectors marketing communications.

1.7 Research limitations/ implications:

In this thesis the data which has been used is not a primary data. All the material has been extracted from secondary data i.e., books of academics and professionals, research papers, journals and online resources.

Only two big organisations, one from each sector, have been undertaken for an analysis which is, arguably, a small sample and might not well represent all kinds of small, medium and large organisations.

All the data about both sample organisations for case study has been gathered from their official websites which can also be argued by someone as limited in some way or another.

1.8 The research question:

Are non-profit organisations becoming businesslike with their marketing communications?

2. Problem- a detailed scenario:

2.1 Non-profit sector acutely important:

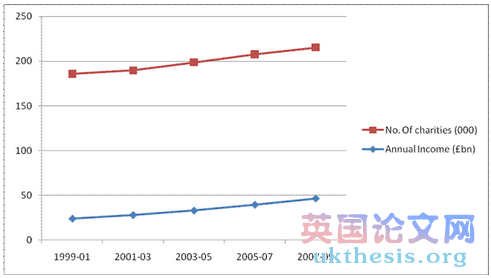

The charity commission, which registers charities in England and Wales, had around more than 150000 charities registered in 1996 with a combined annual income of £16 billion. With an annual income of £16billion there would seem to be no lack of financial support for charities. However the competition for funds among the smaller organisations in particular is fierce and becoming stronger. The growth of charities both in their income and expenditures annually is very interesting and suggests the need for them to be more focussed, more organised, more integrated in communication and innovative at the same time. The graph below shows the progress of non-profit sector in England and Wales over the last decade according to the facts and figures available from Charity Commission UK:

In 1999 the number of charities who registered with charity commission was 163,355 which have reached to 168,354 by March 2009. Likewise, the annual income by March 2009 is £48.400bn which is far higher than 1999 when it was £23.74bn. This huge spike in non-profits number and annual income, which has almost doubled in the last ten years, shows that non-profit sector is a very large and growing part of a society like UK. It also draws attention to a more alarming reality that now NPOs have to compete for funds with ever more powerful and sophisticated communications techniques. A vast range of organisations competing for a share of public charitable funding is growing in extent and diversity. If non-profits are to benefit the causes and the missions they set out to undertake, marketing could be the way to achieve those aims to save a dying child or rescue an endangered species.#p#分页标题#e#

Evidently, in current times, it is hard to refuse the importance of non-profit sector in industrial countries which has become a major economic force. The Johns Hopkins Comparative Non-profit Sector Project, which includes the US, the UK, France, Germany and Japan, the non-profit sector employed on average five percent of total employment in 22 countries. In those countries NPOs have the equivalent of 10.4 million full time employees as volunteers besides paid employment which increases non-profit employment to 7.1 percent of total employment in these 22 countries. In fact, in most countries, the non-profit sector is a product of the last three decades which faced all the developments and change at social welfare legislation, amplified success, demographic and cultural swings and ever-changing role of the state. The non-profit sector has contributed significantly to employment growth during the last three decades. (Helmut, 2000; 6)

The management of non-profit organisations is often ill understood because many authors, academics and professionals argue that it is a building with many rooms and has variety of bottom-line therefore it is fairly difficult to define them as one patent kind (Helmut, 2000; 9, Salamon and Helmut, 1996; 45). The building with many rooms notion not only suggest that this sector has diverse nature vis-a-vis mission and approach but also it points to a larger vision about its differences country to country. NPOs are normally ill-conceived because people think from the wrong assumptions about how non-profit organisations operate. Keeping in view its importance which is no longer the trivial and inconsequential we could understand the need of the problem to be addressed. They are now large and important enough to matter economically and politically, both as organisations and as a sector.

In recent years, however, we have been witnessing almost the opposite trend to what was conceived in past about management for non-profits as a odd to the essence of voluntarism, philanthropy, compassion and a concern for the public good. In this process, many non-profit organisations have come to embrace the language, the management practices, even the culture of the business world, particularly in the United States, but increasingly also in Europe. (Helmut , 2000; 6)

2.2 Complexity of organisations:

Helmut (2000; 13-15) discussed four dimensions for better understanding of diversity in organisational structures in practice around the world. These four elements described below unveil very important points of deliberation:

Tent or palace: There are two types of organisations. A palace organisation concentrates more on control than opportunities, obviousness than invention, and existing solutions than creativity and discourages contradictions and experiments e.g. larger non-profit service-providers, think-tanks and foundations. A tent type likes to go opposite and advocates creativity, initiative and does not stress on harmony or durability of solutions e.g. Civic action groups and citizen initiatives, self-help groups and local non-profit theatres.#p#分页标题#e#

Technocratic culture or social culture: Technocratic view is defined as an approach that organisations are problem-solving machines that emphasise practical show criteria and job accomplishment. Other kind of organisations is akin to families rather than machines e.g. non-profit organisations having religious or political-driven convictions whereas others, such as hospitals or schools, can become more machine-like.

Hierarchy or network: Organisations as hierarchies involve centralised decision-making, top-down approaches to management, nominal control for middle management, and project vertical relations among staff. In contrast, organisations as network emphasise decentralisation and bottom-up approaches in decision-making, and encourage work groups as well as horizontal relations among staff and management.

Outer-directed or inner-directed: Outer-directed organisations prefer to go along other organisations and constituencies; they react to environmental stimuli and take their models and solutions from it. Such organisations adapt to environment changes and seek to control outside influences. Conversely, inner-directed organisations accentuate a more selective view of the environment, focus on their own objectives and world-view.

The complexity of non-profit organisations and their tendency to have multiple bottom lines outline the challenges facing non-profit management. Some will constitute technocratic aspects, while others pull it more into a socio-culture; some constituencies support palace-like organisations, while others prefer to work as tents; some parts of non-profit organisations are more externally-oriented, while others are more inward looking; and finally, some organisational elements are hierarchical, while others are more like networks and loose coalitions. The challenge of non-profit management, then, is to balance the different, often contradictory elements that are the component parts of NPOs. In this sense, it is evident that non-profit management becomes more than just cost-cutting and more than just the application of financial control. Management becomes concerned with more than just one or two of the numerous bottom lines non-profit organisations have.

2.3 Is marketing needful?

Some charities have still to realise the importance of marketing, who assume that to have a good cause guarantees immediate support by the donors. However, there are many organisations with so many good causes attracting public attention that there must be something specific to attract and retain that attention and gain support. The economy influences funding, the context of voluntary action has a clear impact from government policies, and even broader cultural change can also affect non-profit income. Charities need to have a high profile and market their cause to achieve recognition and make an impact on the public consciousness. (Kinnell and MacDougall, 1997; 141-42)#p#分页标题#e#

More than for-profit managers, NPOs executives find themselves in a situation where they must devise ways to expand their revenue streams or face permanent fiscal uncertainty or worse. Most NPOs are in need of an economic market that provides them with resources in the form of revenues. In profit-making organisations, the market is generally made up of the actual or potential consumers of the organisations products. If these consumers buy what the organisations have to sell, management and investors are likely to evaluate the marketing strategy as being successful. This is not necessarily the case with NPOs. (Marios, 2006; 246-49)

If the NPO is excellent, fantastic and astounding, and nobody knows about it or services it offers, how effective is it at doing what it does? This fundamental question forms the basis for the necessity of non-profit marketing. Marketing plays an important role for both sectors. Both sectors may have different bottom lines, objectives or mission marketing is employed to help both reach their goals. Money-making may be the goal for profit organisations and approaching needy people for NPOs but marketing serves both purposes. However, money cannot be ignored as an important factor in NPOs existence and subsistence. It is quite unrealistic to think of a NPO as helpful and beneficial without sufficient funding.

The services provided by NPOs are definitely not free of charge, the handiness is that the users or clients do not have to pay for them but rather funds come from somewhere else to support those functions of NPOs. Nevertheless, the process is not free of competition for NPOs. For example, if an area in terms of funding can no longer support two charity colleges, one is likely to close. It does not mean to say that you wish your competitors or colleagues harm, but sometimes NPOs have to keep in mind the concept of the survival of the fittest. (Morios, 2006; 271-73)

The marketing activity on part of NPOs is not only inspired by their own survival or market share but it serves on many levels. There are business reasons and humanitarian reasons as well. When a non-profit launches a campaign about a problem, need or remedy it does not only benefit its mission but also establish or increase awareness about vital issues in the public. Good marketing and public relations serve both the organisation and the public and in case of NPOs it is beneficial for the public in both ways. It is also helpful for competitors and similar kind of organisations when people are motivated about some disease or potential benefit for them by the effective marketing of an organisation and search for a similar one in their area for convenience. (Morios, 2006; 286-88)

The marketing has several tools which build bridges between the organisation and its stakeholders. Either on small or fairly big scale, organisations whole processes depend on Communications which include a sender, message, channel and receiver. As Schramm (1960) is frequently attributed with originally modelling the communications process as involving following four key components:#p#分页标题#e#

The sender is the originator or source of the message. In practice, agents or consultants may actually do the work on behalf of the sender.

The message is the actual information and impressions that the sender wishes to communicate.

The media are the vehicles or channels used to communicate the message without which there can be no communication. Media can take many different forms.

The receivers are the people who receive the message. (Pickton and Broderick, 2005; 6)

Hence marketing communications is the way to progress for any type of organisation that is keen to survive and achieve its mission. Good marketing communications is not as simple as it looks like apparently. The advertising guru, David Ogilvy was once reported to have employed the word obsolete in an advertisement which (at that time) 43 percent of US women were unaware of (Smith, 1993; 56). A planned and focussed approach for marketing communication has been suggested by many academics and professionals.

2.4 Integrated marketing communications:

Given the most important factor in the whole process to target key audience and motivate them for support, marketing communication seems to play a dominant role. In the past, we all have probably noticed marketing communications under some other commonly used names such as advertising or promotions. Over recent years marketing communications has become the preferred term among academics and some practitioners to depict all the promotional essentials of the marketing mix which involve the communications between an organisation and its target audiences on all matters that may affect marketing performance. (Pickton and Broderick, 2005; 4)

Market communications include a limited area of the process where as marketing communications cover a broader perspective. Marketing involves more groups than just those defined by market members. Many elements have to be involved in the communication process both within the organisation and outside it for marketing to be successful. Pickton and Broderick (2005; 4) elaborate the term marketing communications as ,

“all the promotional elements of the marketing mix which involve the communications between an organisation and its target audiences on all matters that affect marketing performance”.

Smith (1997) proposed this model for integrated marketing communications planning. Fill (2002) developed a more comprehensive marketing communications model MCPF which is a brief version of SOSTAC. Both these models incorporate broader business and marketing factors than simply those that focus directly on the organisation of communications activities.

3. Methodology- an exploratory approach:

The type of this document can largely be defined as an effort to address a topic by undertaking an exploratory research approach. This document basically compares the two, differently presumed, organisations at three different levels.#p#分页标题#e#

First, the discussion begins with a comparison of many different or similar concepts held and described by so many academics and professionals in relation to the structure, objectives, obligations and their practices toward reaching their end purposes.

Second, the necessity and the role of marketing communications for the survival and uplift of the organisation, in both for-profit and non-profit sector, and the impact it might have on overall stakeholder groups of that organisation.

Third and last, the room and application of the most recent and preferred concept of marketing communication which is Integrated Marketing Communications (IMC) in both sectors whether it is purely a business organisation that is following its ultimate goal of making-money or a voluntary organisation involved in welfare and altruistic activities with underlying motive of public good as bottom line for its existence.

In the end two fairly big organisations from health sector, Boots and Cancer Research UK, one is for-profit and other is non-profit respectively, have been being undertaken for case study under a IMC model called SOSTAC. SOSTAC has been adopted by over 3000 marketing managers all around the world as a planning system (Smith and Taylor, 2004; 33). The importance and detail of this model has been discussed later in this document in Chapter 4.6.2 IMC model - SOSTAC. All the data for an analysis, under SOSTAC model, of both these organisations have been extracted from their official websites.

Products known as fmcg (fast moving consumer goods) are typically those we buy from supermarkets and convenience stores, branded products from manufacturers such as Heinz, Kelloggs, Procter & Gamble baked beans, breakfast cereals, shampoos. (Tench and Yeomans, 2006; 503)

Stakeholders are those who influence or can influence the organisation, as well as those affected by it. (Tench and Yeomans, 2006; 241)

SOSTAC (Situation, Objectives, Strategies, Tactics, Action and Control) proposed by Smith (1997). (Tench and Yeomans, 2006; 507)

Fill (2002) developed more sophisticated version of IMC model MCPF (Marketing communications planning framework). (Tench and Yeomans, 2006; 507)

4. Literature a step-by-step comparison:

4.1 Definition of a non-profit organisation:

An organisation can only be non-profit if, after wages and expenses have been taken into account, it is prohibited from dispersing any additional revenue to management or any other controlling personnel such as trustees. There should be no relationship between the control of the operation and the distribution of profits. The not-for-profit sector comprises a wide-ranging disparate number of organisations from arts bodies to health care, charities, churches and local authority leisure services. (Hansmann, 1980; 838-839)

#p#分页标题#e#

Non-profit organisations exist to make a difference in society and are set up to fill the gaps that cannot be met either by the public sector or the market with key importance placed on organisational mission and values (Hanvey and Philpot, 1996; 26). Non-profit organisations share a set of similarities that distinguishes them from government and business entities and makes it reasonable to consider them as a group. Voluntarism is an essential ingredient with the sector based fundamentally on choice rather than compulsion (Hudson, 1999).

The definition of charity and voluntary organisation refers to a wide range of organisations, a building with many rooms (Hanvey and Philpot , 1996; 2: Salamon and Helmut, 1996; 45), which are independent of government control, employ both paid staff and volunteers and receive various types of support from public funds. Since the introduction of a welfare state in the 1940s the number of charities and voluntary organisations has increased enormously, while many have a much longer history (Kinnell and MacDougall, 1997; 141).

Unlike the private sector, there is generally a separation of customers from funders or of “recipients” from “purchasers”. Non-profit organisations are generally accountable to a number of stakeholders, rather than mainly to shareholders as for private companies. Almost all are dependent to some extent on public fundraising. Non-profit organisations operate in a complex environment with a range of legal and financial constraints (such as issues of tax deductibility, governance, etc.), often in addition to other regulation. Many non-profit organisations have an ideological commitment to community involvement and participatory decision-making (Hansmann, 1980; 838-40). Non-profit organisations are subject to a range of success criteria, often with a high degree of ambiguity compared with, for example, “profit” for the business sector. While it is true that most non-profits spend much of their time worrying about money, profit is not the objective of their operations. (Salamon and Helmut, 1996; 61)

Typically, however, goods or services provided by non-profit organisations such as education, health and the arts have both public and private aspects. OHagan and Purdy (1993) argue about a difference also between the public and private not-profit-making enterprise. While private non-profit organisations depend on sales income, donations, grants and/or volunteers, the public organisations are supported by public money in the form of taxation from local and central government sources and/ or funding from other public bodies. (Kinnell and MacDougall, 1997; 3)

Many non-profit organisations are open to innovation and may be highly responsive to changing societal needs. Many non-profit organisations stress the importance of their organisational “culture” and its connection to the organisations cause, leading to perceived constraints in action and decision making (Kinnell and MacDougall, 1997; 8). Non-profit organisations meet the needs of individuals for expressive behaviour. There is usually a high degree of staff commitment to public service and affinity with the organisations “cause”, often shown by an acceptance of lower wages (Hanvey and Philpot , 1996; 29). As a whole, these propositions are not true for government or business entities.#p#分页标题#e#

Kotler and Levy talked about a traditional marketing approach used by commercial organisations which can provide a useful framework for non-profit organisations of many kinds and that the aim was not the introduction of marketing but rather its effective use. Over the last two decades many academics and researchers have concluded that marketing is fundamentally concerned with the exchange processes and relationships between human beings. (Kinnell and Macdougall, 1997; 3)

The board members and major supporters in collaboration with staff define the mission and develop specific performance goals. How can funders or members understand the non-profits vision without a description of its activities and financial goals? What will provide the volunteers with a source of direction? Dreams and aspirations must be explored, examined, and written down in a mission statement. Once the basic philosophical ambitions are understood, financial management becomes easy to work on.

Not all non-profits qualify for tax-exempt status and the means of obtaining, special tax treatment. The confusion arises because the activities of non-profits and for-profits are often the same or very similar. It is important to understand the extent of activity permissible to an exempt organisation.

4.2 Attributes of non-profits:

There is an emerging consensus among researchers in the field that non-profit organisations have the following core characteristics (Salamon and Helmut, 1997; 14):

Organised, i.e. possessing some institutional reality, which separates the organisation from informal entities such as families, gatherings or movements;

Private, i.e., institutionally separate from government, which sets the entity apart from the public sector;

Non-profit-distributing, i.e., not returning any profits generated to owners or equivalents, which distinguishes non-profits from businesses;

Self-governing, i.e., equipped to control their own activities which identifies those that are de jure units of other organisations; and

Voluntary, i.e., being non-compulsory in nature and with some degree of voluntary input in either the agencys activities or management.

Non-profit organisations share the common attribute of being organised for the advancement of a group of persons, rather than particular individual owners like for-profits or businesses. Non-profits include a wide range of institutions. Charities, business leagues, political parties, schools, country clubs, cities, cemeteries, employee benefit societies, social clubs, united - giving campaigns, and a wide variety of other pursuits are all types of non-profit either completely or partially. It can be useful to differentiate between organisations which focus their efforts externally, and those organisations whose work is focused internally, or toward benefiting their members. Sometimes it is useful for the organisation to think of its beneficiaries as clients.#p#分页标题#e#

Non-profits can be divided into different groups as follows: (Jody, 2008; 6-7)

Type 1st: Nonprofits that operate to serve the public good by providing health care, education, culture, and social welfare service to the public (hospitals, schools, libraries, and homeless shelters, for example).

Type 2nd: Organisations that serve both the public and their members (churches, public interest groups, and civic leagues).

Type 3rd: Non-profit membership organisations that are member oriented or that focus their activities on fulfilment of member services (social clubs, business leagues, and labour unions)

A non-profit can utilize the same tools as commercial businesses that perform essentially similar services or sell goods. Though voluntary organisations are not businesses primarily, but they too have objectives, mission and clients, they have to provide services and ultimately they need to finance themselves as much as any other business in one way or another. It is not sinful to be businesslike. Non-profit organisations are not forbidden to earn profit but rather it is only the profit distribution which is not allowed (Hansmann 1980; 838). It is quite similar to ask a non-profit organisation about its strategy as to ask a for-profit organisation. (Handy, Charles, 1990; 4).Likewise, the non-profit can and should patronise its constituents or customers who fall into basically two groups:

Investors or Donors: The people or corporations who provide resources or money to the non-profits in any shape be it a grant, legacy, gift, fund etc.

Clients or customers: Those who are the benefiters or users of services or goods offered by the NPOs.

All three types of non-profits mentioned above must focus on keeping their investors (or donors) and customers (or clients) happy. As in for-profit organisations investors want a return on their money. The return that investors in 1st and 2nd Types of non-profits receive is mostly intangible and the investment is actually donations which are inspired by compassion for the mission. Their benefit and return for their money come through their conscience and a feeling that they are helping someone else. Non-profit organisations exist to make a difference in society and are set up to fill the gaps that cannot be met either by the public sector or the market with key importance placed on organisational mission and values (Hanvey and Philpot , 1996; 26). 1st and 2nd Types of organisations as described above have both investors and customers. 3rd Type of organisations primarily has customers.

Volunteers who invest time must feel important and useful and be shown that their contribution of time is valued and appreciated. Hiring a volunteer coordinator can be an important choice in attracting and maintaining this vital source of financial support. Type 2 and 3 non-profit customers choose whether to participate in the non-profits programs and use the services or goods extended. These non-profits must make every effort to attract customers and give them top priority. Whether one is silver or the other is gold, new and renewing members are an invaluable resource to a wide variety of non-profits. A non-profits attitude toward them can significantly impact its success.#p#分页标题#e#

Although it is not easy to measure this ethereal in the annual budget, it can be invaluable. For those customers receiving the non-profits free or low-cost services, there is an invisible interaction with the investors or contributors. How the non-profit is perceived or evaluated by its customers can impact the attitude of its investors. The financial planners should ask if the organisation treats those to whom it provides services with the highest respect. How does the general public, particularly the non-profits contributors, view the value of its services to the community in aiding the sick, poor, uneducated, or other persons in need?

4.3 Difference between non-profits and for-profits:

A non-profit organisation is distinguishable from a for-profit business in many respects. One distinguishing factor between them is the motivation for undertaking an activity that generates revenue. The fact that non-profits charge for the services they perform is not evidence of profit motive. A hospital may pay all of its costs with patient charges. Whether such a hospital is a non-profit depends on why it was created and how it operates. Is its purpose to promote the general publics health or solely to earn a profit? A non-profit decides to adopt a project because of its value to society or its members rather than its potential to generate monetary profits, although one worthy project may be chosen over another based on revenue expectations.

Accordingly, the challenges in achieving financial success may be considerably more daunting for non-profits than for for-profits.

4.3.1 Donors versus Investors:

Charities and voluntary organisations have two potential constituents without whom they are incomplete and useless: the clients for whom the charity exists to serve and benefit and the donors without whom the charity would not exist. A NPO does not only have to grab potential donors but also needs to maintain good and credible relationship in a long term is imperative as well. To reach and motivate potential donors by means of effective and focussed marketing is as needful for a NPO as is for a business to attract and provoke an investor for some project or product. A non-profits need for capital, or unrestricted and available-to-spend, funds, to carry on operation is analogous to a for-profits: Capital provides the financial underpinning to bridge gaps in the flow of funds and to ensure that financial obligations can be paid in a timely fashion.

The economic rewards customary in business — dividends, interest, and capital appreciation — are not available to those who invest in nonprofits. The standards used by a non-profit supporter to measure returns on their money are very different from a for-profit investors. The tools for measuring success, however, are similar. Financial indicators that evidence goals accomplished can be used as a measure. The prosperity of a non-profit can be evaluated by counting the number of children clothed and fed during the year, by comparing the per-patient costs this year with last, or by studying the number of new professionals qualified due to a business leagues training efforts.#p#分页标题#e#

Philanthropists who donate capital funds to a non-profit to obtain buildings or to establish endowments certainly expect the organisation to “profit” or benefit from the gift in a sense. In donating capital, the donors are investing in the mission. They recognise and intend their capital to be an unselfish gift directed outward in service of a public purpose. In effect, nonprofits operate on a linear model of money operations. Much of the money they receive is just such one - way money — donations made out of pure generosity, for which nothing is provided or expected in return. Privately owned businesses, in contrast, operate on a two-way or circular model. For-profit organisations generally receive funds from investors who expect something in return. In for-profits the money goes back to the owner and shareholders in shape of profit unlike NPOs. (Jody, 2008; 11-12)

4.3.2 Clients versus customers:

Traditionally, some non-profits charge for the goods and services they provide to their program service recipients; hospitals and universities. Many non-profits provide free services that are financed by a complex variety of donations, grants, and other income sources. Recipients of a non-profits goods, services, or monetary grants in aid are distinct from, but similar to, a for-profits customers. A prosperous non-profit most likely treats its program - service constituents — the poor, the sick, the culture seekers, the students — as a business would its customers. It values their patronage and caters to their needs. Whether the non-profit charges for the goods and services provided or furnish them on a reduced or no-fee basis, the methods used by a for-profit in providing similar goods can be observed. (Hansmann, 1980, 866-68, Jody, 2008, 11-13)

Some operate with volunteer labour and sell or distribute donated goods. One important distinction is the fact that it may be impossible for some organisations to charge for the services provided. The public depends on immediate and free response from its fire-fighters or policemen and women, for instance. Having library doors open in the evening for students to do research is expected.

When a non-profit does charge, the charge may not necessarily cover costs of the service; for-profits only sell things for less than cost if forced to do so by market apathy. Obviously, it is more difficult for non-profits to raise prices, partly because of the publics expectations and partly because of the economic need of the organisations constituents. Ironically, the tight budget situation created by cuts in government funding typically comes during depressed economic periods or when new tax rules reduce or remove the tax benefit of contributions, thus discouraging philanthropy. Suffice it to say that a non-profit is significantly different from a for-profit in many ways, even though its operations and financial decisions may often appear to be similar.#p#分页标题#e#

4.3.3 Staff paid employees versus volunteers:

The staffs are very vital participants in any kind of an organisation. Therefore, both the sectors whether profit or non-profit eventually need people in their organisations to for their plans and projects to be operationalised in an organised and efficient manner. Most of the NPOs have both paid and voluntary staff for different operations to plan and be done though the major work force of NPOs depends upon volunteers who serve some cause by their own choice. Organisations that aim at doing business only for just business with no underlying mission or public good constitute all paid employees.

In rare cases, a for-profit organisation might hire some volunteer when it is pursuing some charity project in hope of promoting its better and humane image before general public. But the motive behind this charity project of for-profit would be opposite to NPO because it would be undertaken to promote the brand or product or the good will ultimately to serve their money-motive by attracting more and more customers.

4.4 For-profit tools:

Although businesses do not often show movies for free or feed the poor, they do run much other kind of projects which are also operated under NPOs. These types of projects include schools, hospitals, theatres, galleries, publishing companies, and conduct other activities that are also undertaken by non-profit organisations. The non-profits reason for doing some project and the ultimate benefit from the capital is definitely different. Nonetheless, the financial issues seem similar; both types of organisation can use similar financial tools. There is no reason why a non-profit cannot use a for-profit model to manage its financial affairs in a similar kind of project. A non-profit that operates in a businesslike fashion may be more likely to succeed. Some of the useful tools include (Jody, 2008; 13):

Business plan: Non-profits can develop a long-range business plan based on market surveys, cost estimations, and strategic goals. Like a for-profit, a NPO can:

Collect reasonable reserves by earning in excess to what it spends

Be directed about who makes decisions

Adopt positive financial practices for both planning and reporting

Critical analysis of decisions: A non-profit can compare its working and planning by putting a for-profit in its place and analyse its possible handling of the project in order to make a similar financial decision. In considering a question, the non-profit might ask:

What would make this non-profit make money and reach its goal?

How would an entrepreneur handle if the same situation arose in his or her business?

Last, but not least, if the non-profit had stockholders, would they approve the recommendations being proposed?

Traditional management tools: The management tools for getting to organisational objectives are the same whether the objectives are business-oriented or mission-oriented. Like for-profits, a non-profits management tools include:#p#分页标题#e#

Forecasts, budgets, and ratio analysis

Well-designed and timely financial reports

Defined lines of communication and responsibility

Cash-flow monitoring system

Efficient organizational structure with fiscal controls

Identification of the target served (i.e., the customers or constituents)

Clearly defined line of business (mission) (Jody, 2008)

4.5 Is profit-making allowed to NPOs?

A non-profit organisation is, actually, a type of organisation that is not allowed to distribute its net earnings, if any, among individuals who operate it in some way or another, such as members, officers, directors, or trustees. Net earnings mean pure profits i.e. earnings in excess of what is necessary to pay for services provided to the organisation; in general, a non-profit is free to pay reasonable compensation to any person for labour or service that he provides, whether or not that person is a part of immediate control in the organisation. (Hansmann, 1980; 838)

For many, the term non-profit implies a ban for the receipt of revenues in excess of expenditures. Such concepts suggest that a non-profit should always be losing money all the time and has no right to get a profit even if it is required for the operation and progress of its mission (Jody, 2008; 8). It should be noted that a NPO is not barred from earning a profit. Many non-profits in fact consistently show an annual accounting surplus and the prohibition is only applied on distribution of profit. Net earnings, if any, can be utilised whichever way deemed fruitful in order to take steps ,e.g. launch of a new project to earn money, to enhance or support the underlying mission of the NPO (Hansmann, 1980; 838, Jody, 2008; 8). The pursuit of profit in the normal sense is not the primary motivation of nonprofits but a non-profit can operate without a profit motive and still produce what many think of as a profit.

4.5.1 Meaning of profit:

The commonly conceived meaning of profit for an organisation is the money in excess of the total investment by and owner or investor and calculated through the sales factor of a product or service. This is not essentially applicable to NPOs where money-making is not the primary goal and the profit does not return to the chief executive or the board of directors. Profit for a non-profit can constitute anything that is meaningful and indicative for the organisations progress and advancement toward its underlying mission.

Profit for a non-profit does not always come just from the bottom line but rather it may be measured in terms of the number of books published, enhancement of the professions public image, discovering a cure for a disease for a research organisation. If a hospital installs a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machine to offer better health care, it should reasonably expect the machine to pay for itself plus provide a constant flow of excess revenue, or profit. The hospital may use such profits to improve its diagnostic capabilities or use them to purchase a building, to expand other departments, or for any other valid reason serving its underlying non-profit purposes. (Jody, 2008; 8)#p#分页标题#e#

The directors or trustees serve as stewards of the funds to assure they are devoted to meeting the socially desirable goals chalked out in the mission of the NPO. The income, or profit, is not distributable to its members, directors, or officers. Just like a for-profit business, the non-profit can pay salaries and employee benefits to its workers (including its directors), as long as the pay is reasonable in relation to services performed.

4.5.2 Profit restrictions:

NPOs should not amass excess funds, or capital, as long as such funds are devoted to the mission on the basis of a few or many, if any, reasons — legal, ethical, or otherwise. Two authoritative interpretations of the term non-profit must be taken into serious consideration for clear evaluation:

“The State of Texas says a “non-profit corporation means a corporation no part of the income of which is distributable to its members, directors, or officers”. Similarly, the State of New York provides a two-prong test for determining whether a corporation is qualified to be treated as a non-profit entity: a) New York non-profits must be formed for a non-pecuniary purpose and, b) No part of their assets, income, or profit is distributable to, or may inure to the benefit of, its members, directors, or officers with certain exceptions otherwise permitted”. (Jody, 2008; 9)

A non-profit is distinguished from a for-profit (or business) corporation primarily by the absence of stock or other indicia of ownership that entitle their owners a simultaneous share in profits and control.

“In the corporation law of some states, the non-distribution constraint is accompanied or replaced by a simple statement to the effect that the organisation must not be formed or operated for the purpose of pecuniary gain. Often such a condition as applied is equivalent to the non-distribution constraint. Occasionally, however, it is interpreted more restrictively to mean that an organization may not be incorporated as a non-profit even if it is intended to assist in the pursuit of pecuniary gain in a more indirect manner”. (Hunsmann, 1980; 838-39)

The word pecuniary simply means “that which relates to money”. Clearly, a non-profit must receive, hold, and use money to operate. The NPOs mission or goal or having money must not be solely to generate more money. Money can be its means, but not its end. Receiving, spending, and accumulating money, the New York law requires, must not be a NPOs mission and that mission must be something else which is altruistic in nature and useful for public.

“The American Institute of Certified Public Accountants Audit Guide for Not-for-Profits states that the term not-for-profit is not intended to imply that a voluntary health and welfare organisation cannot obtain revenues in excess of expenses in any particular period; rather, it implies that the organisation is not operated for the financial benefit of any specific individual or group of individuals”. (Jody, 2008; 9)#p#分页标题#e#

A non-profit organisation must decide about the excess revenues, or profit, for the year that should reasonably be accumulated. Though the tax code contains no numerical restriction on the amount of fund balances a tax-exempt organisation can preserve, but still this decision may affect the attitude of NPOs funders. The money must be spent during the coming year because if it does not, the organisation whose programme can be halted due to funds shortage may justify its right for support in the first place. (Jody, 2008; 10)

4.5.3 Profit is indispensable:

The wrong conception that a non-profit organisation must not pursue ways to accumulate profit can be disastrous for its existence and its mission as well which ultimately is a door where needy can get themselves supported for, sometimes, very little or mostly no charges. True enough, an NPOs top priority is not to produce profits — it dedicates itself to carrying out a mission to benefit others. Yet profit can enhance the ability to perform its mission just as the year-end profit distributed as dividends to shareholders influences a for-profit common stock market price. (Jody, 2008; 10-11)

4.5.4 Tax-exempt status:

Many non-profit organisations enjoy special freedom of tax-exempt under state and federal taxation. It is often suggested that such tax benefits act as a strong inducement for the organisation of activities along non-profit rather than for-profit lines. Although tax considerations are probably far less important than is usually perceived. A large class of NPOs is exempt from the federal income tax. Not all of them, however; rather, exemption applies only to those that aim at serving a specified, though broad set of purposes.

For example, while non-profit hospitals and educational institutions are exempt, automobile service clubs are not. Whether this exemption has had a meaningful impact on the types of activities undertaken by nonprofits is questionable. To begin with, by the time the corporate income tax first appeared in the late nineteenth century, NPOs already were well established in many of the areas where they are found today. Furthermore, the tax liability of many nonprofits under the corporate tax would probably be modest even if they were not exempt. Finally, and perhaps most important, over time the definition of the categories of nonprofits that qualify for exemption has followed the expansion of nonprofits into new fields, rather than vice versa. The tax code did not set forth in the beginning a well-defined set of sectors in which nonprofits could qualify for exemption, generating nonprofits in those sectors. (Hansmann, 1980; 882-83)

However, tax exemption obviously gives NPOs a competitive advantage that they would not otherwise entitled to with respect to for-profit firms, and thus probably influences the overall degree of non-profit development even if it is not vital in deciding the industries in which that development takes place.#p#分页标题#e#

4.6 Marketing an essential area:

As McCort (1994) describes, the rate at which non-profit organisations, particularly voluntary, religious and charitable institutions, are adopting the marketing concept and integrating fully the principles and practices which could benefit their operation. The cultivation and development of long-term relationships with consumers is recommended as a useful strategy to overcome the difficulties encountered by the unique characteristics of non-profit services. A relationship marketing strategy is particularly appropriate for voluntary, religious and charitable organisations in dealing with the characteristic dual nature of their public the donors and the beneficiaries. The development and maintenance of long-term relationships with donors is crucial for the survival of these organisations. The motivation and encouragement of donors to continue their loyalty and support with intangible benefits is challenging process and can be facilitated by building on the value of the relationship rather than the transaction itself. (Kinnell and MacDougall, 1997; 4-5)

The satisfaction of customers is the most important goal of the non-profit public service or voluntary organisations. It is important to note the reactions of the customers and get experience from suggestions/complaints in order to improve the services and other organisational needs. Staff and organisation as a whole should learn from customers reactions and remedy past mistakes. All this include a range of communication management involving both staff and customers of the organisation. (Kinnell and MacDougall, 1997; 8-9)

An essential element in the structure of communication strategy in both for-profit and non-profit organisations is achieving and maintaining quality of products or services. A range of definitions indicates the breadth of issues requiring attention in delivering a quality service (Oakland, 1995): The totality of features and characteristics of a product or service that bear on its ability to satisfy stated or implied needs; The total composite product and service characteristics of marketing, engineering, manufacture and

maintenance through which the product and service in use will meet the expectation by the customer; Conformance to requirements. (Kinnell and Macdougall, 1997; 17)

A continual awareness of how a service stacks up against accepted standards has to be built into the quality assurance systems of the organisation, and seen as an essential element in the marketing strategy. Consistence in service delivery is also seen as essential, in order to sustain a relationship between the customer and the service, and to develop and maintain relationship. (Kinnell and Macdougall, 1997; 17)

A key purpose for existence is the financial planning for nonprofits. It is based on the philosophical ambition of persons coming together to carry out mutual goals. The end purpose of a non-profit is based on hope, sometimes on prayer, and almost always on dreams. Dreams, being insubstantial, can be idealistic and can make financial planning a risky venture. The goal is to collect as much funds as possible to withstand the underlying mission. Another need is to stretch and balance precious resources to best accomplish the dream. Together, the two functions — performing the mission and providing the requisite resources — work as a team to sustain the non-profits life. (Jody, 2008; 1)#p#分页标题#e#

Although idealistic aims guide the planning process and prescribe a non-profits priorities, accomplishment of the goal can be improved with smart planning. Similar to the income tax rules concerning tax-exempt financial planning for non-profit organisations demands acknowledgment that the special character, language, and tools relevant to nonprofits be understood alongside language and concepts applicable to for-profits. It is valuable to consider what would make it prosper and flourish like a business when working with a non-profit organisation,.

4.6.1 Integrated Marketing Communications:

Kotler (2003; 563) proposes his concept about integrated marketing communications as, “a way of looking at the whole marketing process from the viewpoint of the customer” (Pickton and Broderick, 2005; 3). Schiltz and Kitchen (2000) define IMC as a strategic organisation course of action to plan, develop, implement and calculate coordinated measurable, persuasive brand communication programmes over time with users, clientele, prospects and other targeted, relevant outer and in-house audiences (Tench and Yeomans, 2006; 504). Betts (1995) argues that IMC is the strategic process which helps in selecting elements of marketing communications which will successfully and cost-effectively stimulate dealings between an organisation and its existing and potential customers, clients and consumers. Duncan (2002) refers IMC to a process for managing the customer relationships which goad brand value and a cross-functional process for creating and cultivating profitable relationships with all stakeholders by strategically managing all messages conveyed to these groups and encouraging data-driven, focussed discourse with them. (Pickton and Broderick, 2005; 25)

Corporate communications is another term that is also in vogue. The variation in the use of terminology is very confusing but not unexpected when we consider that so many people are involved in the vast application of communications, each with their own interests, partiality and predispositions. It is certain that some will use one term or depiction in preference to another. This eventually needs to be realised and accepted. It is important, however, that distinctions between these terms can be made so a large extent for understanding. (Pickton and Broderick, 2005; 25-26)

There can be two ways of differentiating between marketing communications and corporate communications. One way of understanding the problem is to consider that the broad term ought to be corporate communications of which marketing communications is a part. In this way, it can be perceived that corporate communications includes marketing communications andsome other types of communications as well, that can be, communications which are not linked to marketing activities. So, perhaps, it can be argued that communications other than marketing purpose with employees or shareholders or other stakeholders would be examples of corporate communications but not marketing communications. Hence we can say the difference is not in the concept and materialisation of the concept of communications but actually in the content of communications. (Pickton and Broderick, 2005; 5-7)#p#分页标题#e#

Blauw (1994) defines corporate communication as the integrated approach to all communication formed by an organisation focussed at all relevant target groups and Van Riel (1995) differentiates that corporate communication constitutes three main types; marketing communication, organisational communication and management communication. Management communication is understood by Van Riel as the most important of the three, and comprises communications by managers with internal and external target groups. Organisational communication he defines as a heterogeneous group of communications actions including internal communication, corporate advertising, public relations and other communications at the corporate level. Marketing communications, which Van Riel states, takes the largest share of the corporate communication budget, consists primarily of those forms of communication that support sales of particular goods and services; as such he presumably restricts marketing communications to the product level only. (Pickton and Broderick, 2005; 5)

4.6.2 IMC model SOSTAC:

There are many approaches to chalk out a marketing plan and implement those systems for capturing the goals and objectives set by an organisation. Among all these different approaches some elements happen to be in common and are the key constituents of almost all systems operating toward a marketing communications plan. SOSTAC has a simple, practicable and comprehensive set of elements which can be applied to any type of plan either corporate, marketing or marketing communications plan (Smith and Taylor, 2004; 32). A brief detail of SOSTAC is as follows:

S Situation (where we are now?)

This level is the foundation of this model to be handled with inordinate concentration and focus. It includes all the factors which are related to the organisation in some way or another. For instance, SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats) and PEST (political, economic, social and technological) analyses of the organisation are to be employed, not in so much depth, but in relation to marketing incentives.

O Objectives (where do we intend to reach?)

After analysing the situation in which the organisation actually stands with the help of researching secondary and primary sources a clear picture comes up which answers the question: where we are now? Then it is time to set and define the objectives of the organisation as specifically as possible to make an implementation and control easier. SMART (specific, measurable, actionable, realistic and time specific) concept can be helpful in testing objectives.

S Strategy (how do we get there?)

This step is over-arching with tactics or we can say that a concise and outline description of communications tools constitute a strategy. Strategy can select certain communication tools which can be more effective regarding your type of organisation or goals. It can also set the arrangement of communications tools for best time and cost-efficient results.#p#分页标题#e#

T Tactics (the detail of strategy)

Tactics are the details of strategy and selection of different communications tools. There are so many tools which are included in a famous term communication mix in marketing communications. For instance, advertising, PR, direct mail, exhibition, internet, word of mouth etc., fall in that category.

A Action (implementation of tactics)

Action includes implementation of tactics chosen to steer the strategy. Implementation is always harder than to what it seems like before as a plan. Implementation of marketing communications tactics needs to get other people (staff, agencies etc) to perform and accomplish targets within time and budget.

C Control (measurement, monitoring, reviewing and modifying)

This stage is overlapping with the previous stage of action. When the plan is under implementation stage, results and strategy are analysed and monitored if it goes unexpected. If it happens, the management should be doing amendments to the strategy, tactics or the people involved in carrying out those operations.

The Action and Control stages are basically serve the purpose of monitoring the tactics and results. If the results are appropriate and similar to expectations of the plan and a progress is happening, it is considered as a successful plan.

SOSTAC offers a structure upon which a comprehensive plan can be built and tested as well. Below are some views on how experts feel about SOSTAC as a planning model for IMC (Smith and Taylor, 2004; 35):

“Professor Philip Kotler: SOSTAC is a system for going through the steps and building a marketing plan.

Sam Howe, Director of CATV Marketing, Southwestern Bell: SOSTAC is a great approach for anyone going ahead and building a market plan.

David Solomon, Marketing Director, TVX: It appears that we are following the principles of SOSTAC.

John Leftwick, Marketing Director, Microsoft UK: We use SOSTAC within our own marketing planning.

Peter Liney, Concorde Marketing Manager: I think SOSTAC is very good in terms of identifying. If you like, major component parts of what youre doing in marketing.”

This is the last opinion of Peter Liney, Concorde marketing manager which motivates this model to be undertaken in this research document for studying cases both profit and non-profit organisations.

5. Case studies:

5.1 Case no.1 - Boots:

5.1.1 Situation:

Boots is the UKs leading pharmacy-led health and beauty retailer. Boots is a member of Alliance Boots. Alliance Pharmacy and Boots merged together to create a new Boots business with around 3000 stores around the world and 2,600 in UK only from local community pharmacies to large destination health and beauty stores. Boots has its roots in the mid-19th century when John Boot, an agricultural worker, moved to Nottingham to start a new business. He opened a small herbalist store on Goose Gate in 1849, from which he prepared and sold herbal remedies.#p#分页标题#e#

Alliance Boots is a major employer in the UK and many other countries. At the year end the Group, including their associates and joint ventures, employed over 115,000 people in more than 20 countries. At the end of the year net borrowings (defined as cash and cash equivalents, restricted cash, derivative financial instruments and borrowings net of amortised prepaid financing fees) were £9,034 million which was £8746 million last year. Shareholders equity increased during the year by £169 million to £4,182 million at the year end. Boots UK recent revenue were £6343 million with a trading profit of £628 million and International were £804 million with a trading profit of £45 million.

5.1.1.1 SWOT analysis:

Governments are implementing measures to encourage doctors to prescribe more generic medicines in order to reduce costs. Alliance Healthcare and Pharmaceutical Wholesale Division, use its scale and international sourcing capabilities to secure lower prices.

Better cash margins on generics in a way which legislation typically does not permit for branded products, leaves them to take advantage of this continuing trend.

Governments are increasing the number of medicines available for retail purchase to encourage consumers to pay for medicines for minor ailments, rather than going to their doctor for a prescription.

With its healthcare expertise, Boots is well placed to secure a large share of this new market, in part through developing better value own brand product ranges which customers trust as substitutes for leading brands.

Governments are seeking to provide more healthcare services in the community in a cost effective way. Pharmacy is well placed to provide many services, such as medicine checkups, weight management programmes, smoking cessation advice and flu vaccinations.

In time cost pressures on governments are likely to lead to deregulation of pharmacy ownership in more European countries, to allow multiple ownership alongside wholesale, although the timing of this remains highly uncertain.

The huge success of No7 Protect & Perfect Beauty Serum highlights the latent consumer demand for beauty products which are validated by scientific evidence.

Boots, along with certain other leading manufacturers of beauty products, continue to focus our product development activities in this select area of the beauty marketplace.

An increasing number of branded pharmaceutical manufacturers are seeking further efficiencies and control by switching from selling via multiple pharmaceutical wholesalers to either selling direct to pharmacies (using relatively few wholesalers as distributors, such as Alliance Healthcare, to deliver the product, invoice customers and collect payments), or selling via a select number of national wholesalers, such as Alliance Healthcare. Boots expect this trend to continue in the coming years.#p#分页标题#e#

In European pharmaceutical wholesaling markets, Boots expect consolidation amongst wholesalers to accelerate as regulatory and market changes put increasing pressure on small regional wholesalers.

5.1.2 Objectives:

At Boots, their mission is to be a world-class pharmacy-led health and beauty retailer. With the help of their suppliers, it is one they can make a reality every single time their customers encounter the Boots brand.

They understand just how important it is for them to make sure their stores are a great place to shop.

Ensuring that their products are available on the shelf for their customers to buy is an essential part of their concerns, so they continue to invest in the modernisation of their supply chain.

Their purpose is to help their customers look and feel better than they ever thought possible.

Their customers are at the heart of their business. They're committed to providing exceptional customer and patient care, be the first choice for pharmacy and healthcare, offer innovative products 'only at Boots', with great value our customers love.

Their people are their strength and they tell us that Boots is a great place to work. They aim to always be the employer of choice, attracting and retaining the most talented and passionate people.

They're currently embarking on a major expansion of the Boots brand by rebranding our community pharmacies, Alliance Pharmacy as 'your local Boots pharmacy'.

They will continue their traditional focus on healthcare and dispensing, with the addition of Boots healthcare and Boots own brand product range. This is the largest expansion of the Boots brand ever.

5.1.3 Strategy:

Boots is the largest pharmacy chain in Europe with an excellent reputation for differentiated health and beauty products and customer care. Their strategy is to develop Boots into the worlds leading pharmacy-led health and beauty retail brand, focused on helping people look and feel their best. The key steps they are taking in the UK to execute their strategy are:

The Groups strategy is to focus on its two core business activities of pharmacy-led health and beauty retailing and pharmaceutical wholesaling and distribution. This includes growing their core businesses in existing markets, continuing to deliver productivity improvements and other cost savings, and pursuing growth opportunities in selective new high growth markets. This strategy is underpinned by a continued focus on patient/customer needs and service, the Groups portfolio of excellent and well trusted brands and products, and their strong financial disciplines recently established a Boots commercial academy to ensure that they have the best people supporting and developing their customer offering.#p#分页标题#e#

The number of pharmacists and beauty consultants to provide fast, friendly service and expert customer care.

They aim at re-branding over 1,000 outlets into “your local Boots pharmacy” and relocating more Boots stores/pharmacies to improved locations. They are also increasing the number of Boots stores through new openings and pharmacy acquisitions and doubling the number of Boots Opticians practices through the re-branding of Dollond & Aitchison.

They are improving the product knowledge of their people through weekly e-learning sessions.

They are improving their customers in-store shopping experience by consistently providing best in class customer care and service. This is being partly achieved by operating efficient walk-in prescription services staffed by friendly, knowledgeable and accessible pharmacists, and faster till service.

Customers experiences are being further enhanced by better in-store product availability through investment in a more efficient logistics network, refitted older stores, and redesigned store layouts to make it easier for customers to find what they want.

They are working on creating a compelling multi-channel health and wellbeing consumer offering. Initiatives include making shopping at boots.com easier, expanding product ranges available on-line and rolling out our “order-on-line collect-in-store” concept.

They are also going to launch a BootsWebMD consumer health and wellness information portal in 2009 in partnership with WebMD, the leading US healthcare information portal.

5.1.3.1 International strategy:

The key steps we are taking in their International health and beauty markets to execute their objectives are:

Opening new stores in markets where Boots is already well established, including the Republic of Ireland, Norway and Thailand.

Developing country specific Boots branded trading formats to meet local needs, including the roll-out of the successful “Boots apotek” pharmacy concept in Norway. They also started to test a “Boots apotheek” pharmacy concept in The Netherlands.

Selective franchising of the Boots pharmacy-led health and beauty retail proposition in areas such as the Middle East.

In addition they are considering, over time, to establish Boots pharmacy chains in new countries where legislation permits and it makes economic sense to do so. Alliance Healthcare is one of Europes largest pharmaceutical wholesalers with an excellent reputation for service. Their strategy for Alliance Healthcare is to be the worlds leading wholesaler and distributor of pharmaceutical products, working in partnership to provide added-value services for pharmacy and manufacturer customers. The key steps they are taking to execute their strategy include:#p#分页标题#e#

Ensuring that they continue to deliver an excellent core service to all their customers. Typically they deliver prescription medicines to pharmacies at least twice a day on a just-in-time basis to meet patients needs.

In-stock availability, accuracy of picking and reliable van deliveries within set time periods are essential to achieve this consistently.

Evolving their business model to meet changing demands from manufacturer and pharmacy customers for new services.

They aim to do this through winning direct-to-pharmacy distribution contracts, achieving preferred status for selective wholesaler contracts, expanding their pre-wholesale and contract logistics services, developing our contract sales forces, and developing innovative added-value services such as the Alphega Pharmacy concept.

Increasing efficiency and driving down costs by growing market share where it proves cost effective to do so, continuing to implement their Division-wide business improvement programme and acquiring businesses to increase scale, such as Depolabo in 2008/09.

Differentiating their product offering. They are achieving this through a series of initiatives which include the development of Almus, their exclusive range of generic medicines, and the extension of Alvita, their branded healthcare product range.

They have also successfully launched the Boots Laboratories Serum7 skincare range for independent pharmacy customers in France, and in Portugal through their associate, and are planning to launch this range in other countries in 2009/10.

Extending their capabilities into high growth specialty medicine/homecare markets, which included the acquisitions of Megapharm and Central Homecare in 2008/09.

Entering new geographical markets where stable regulatory environments, large populations, growing healthcare expenditure, scope for wholesaler consolidation and the right management can be found, such as in Russia and China in recent years.

Alphega Pharmacy is a leading network of independent pharmacists, now operating in six countries with around 2,200 members.

Positioning:

Boots store formats are:

Flagship store: The widest range of products and services, big on new beauty.

Local pharmacy: Healthcare-focused community stores. Work closely with Primary Care Trusts.

Health and Beauty: Edge of town, convenience and high-street stores.

Airport: for travelling customers' last minute needs.

5.1.4 Tactics:

The retailer has converted more than 200 pharmacies out of a total 1,100 to Your Local Boots Pharmacy fascia and has now stepped up conversions to about 80 to 100 a month.

Alliance Boots director of stores Simon Roberts (November 6, 2008) said: “We will have all the small pharmacies converted by summer next year and the response has been great. Customers like having Boots own-brand products alongside their usual pharmacy services.”#p#分页标题#e#

Roberts also (November 6, 2008) said that Boots is also trialling an order online and collect in-store operation will be available in 1,270 shops by Christmas. It has also linked its store staff bonus schemes to its customer research.

During the year, Alliance Boots has invested in new products such as its No 7 Protect & Perfect Foundation range and No 7 Extreme Length Mascara.

In 2005 three simple television ads by Mother are at the centre of a new campaign to position Boots as the expert in health and beauty retailing. In this ad, "teardrop", an exploding teardrop is shown in reverse, trailing back to the seven-year-old boy who has cried after cutting himself. At the end of the ad, which promotes Boots plasters, he runs off to play once more. The voiceover is by Desmond Morris, with other ads showing a transparent baby and a plant transforming into a beautiful woman.