美国留学生市场营销论文定制-关于丰田汽车与美国汽车企业大规模定制市场工作的比较研究-Toyota Motor Compa

时间:2011-08-02 13:46:17 来源:www.ukthesis.org 作者:英国论文网 点击:358次

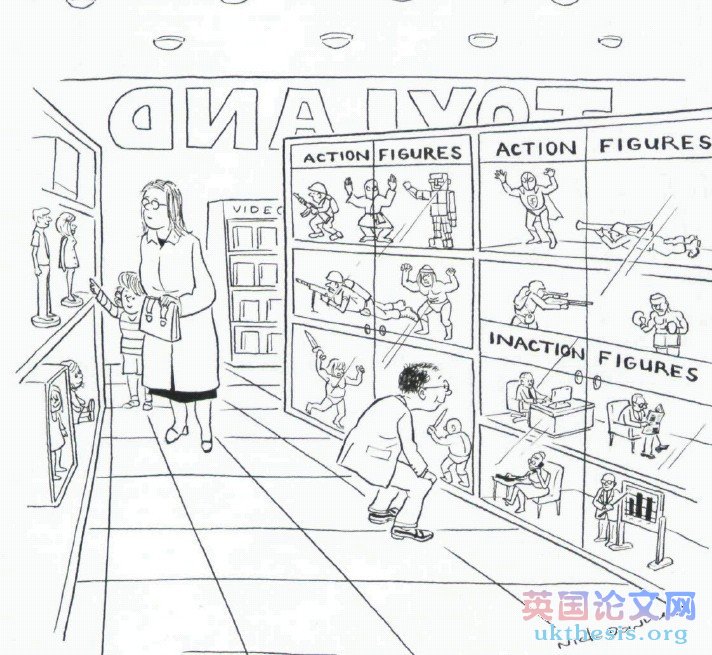

美国留学生市场营销论文定制Not just an extension of continuous improvement,mass customization calls for a transformed company. by B. Joseph Pine II, Bart Victor, and Andrew C. Boynton  Continuous improvement can certainly he a subsetof mass customization. The autonomous operatingunits within a mass customizer can andshould strive to continuously improve their processes. But as Toyota, for one, seems to bave finallyrealized, mass customization generally cannot bea subset of continuous improvement. One of tbe main causes of Toyota's recent prohlemswas that it had been pursuing mass customization but had retained tbe structures and systemsof continuous-improvement organizations. By doing this, Toyota ended up not succeeding atmass customization and, at tbe same time, underminingits continuous-improvement efforts. For example, Toyota assumed that its work forcehad attained the skills needed to handle productionof its rapidly growing range of product offerings. But when the frequently cbanging tasksbutted up against tbe limit oi workers'capabilities, managers did notrealize tbat the problems stemmedfrom a failure to transform the organization. Ratber than developing tbeloose network necessary to make amass-customization organizationwork, Toyota managers turned tomachines. Over time, this ended up weakening the skills of the workers and thus violated an essentialtenet of continuous improvement. It also caused internalfriction. One action Toyota took was to invest heavily in robots. But as one Toyota manager later commented, "Robots don't make suggestions." Toyota also installed monitors at some stations along the assemblyline tbat told workers bow to put togethera particular car. And the company installed computer-#p#分页标题#e# controlled spotlights illuminating the binscontaining tbe rigbt components. These measures deprived employees of opportunities to learn andthink about the processes and, tberefore, reducedtheir ability to improve them. Another big problem at Toyota was tbat productproliferation took on a life of its own. Like mindlesscontinuous improvers, engineers created teebnically elegant features regardless of whether customerswanted the additional choices. In mass customization, customer demand drives model varieties. A third problem arose wben Toyota's management,in its pursuit of low-cost customization, pushed product development teams to use morecommon components across its models. At Toyota,project leaders have overall responsibility for the development of a given model, but separate teamsdevelop individual components, such as brake systemsor transmissions, which ideally will be usedin several models. Project leaders felt that the intensifyingpressure to share components was forcingthem to compromise their models, and they began to resist. Eventually, the company couldn'tachieve targeted levels for sharing design expertise,components, and production processes, and overallproduct development costs rose. Other companies bave also heen attempting toachieve mass customization with less than optimalresults. Some of their experiences highlight the potentialpitfalls companies can encounter in tryingto make this leap. • Nissan, Mitsubishi, and Mazda have run intomany of the same problems that hurt Toyota. Nissan,for example, reportedly bad 87 different varietiesof steering wheels, most of which were greatengineering feats. But customers did not want Toyota created technicallyelegant features regardless ofwhether customers wanted them.many of tbcm and disliked having to choose fromso many options. D Amdahl, which built its business on a low-cost strategy hut never made the move to continuous improvement, adopted a goal similar to Toyota's: deliver a custom-built mainframe in a week. However, Amdahl did not achieve its objective througb flexible process capabilities, a dynamic network, or anything else resembling mass customization. It stocked inventory for every possible combination 110 HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW September-October 1993 that customers could order, an approach that ended up saddling it with hundreds of millions of dollars in excess inventory. • Dow Jones, tbrougb the Wall Street fournal and its other news-gathering resources, has a storehouse of information that it can customize and then deliver in a number of ways, including newswires, faxes, and on-line computer systems. Dow Nissan, Mitsubishi, and Mazda ran into many of the same problems that hurt Toyota. Jones, however, has not yet found the right formula for packaging services at a low price that would allow it to increase its share of the market.#p#分页标题#e# We suspect that two factors are responsible. Dow Jones seems to he trying to push a somewhat customized product out the door ratber than first determining what customers truly need and how they want it delivered. The company also doesn't appear to have developed the organizational capabilities that would enable it to lower its costs enough to expand the still emerging market for customized information. Despite the fact so many companies are struggling, scores of otbers are joining the quest. Tbe appeal is understandable. Mass customization offers a solution to a basic dilemma that has plagued generations of executives. Breaking New Ground Until the widespread adoption of continuous improvement began about 15 years ago, either/or dichotomies dictated most managerial choices. A company could pursue a strategy of providing large volumes of standardized goods or services at a low cost, or it could decide to make customized or highly differentiated products in smaller volumes at a high cost. In other words, companies bad to choose between being efficient mass producers and being innovative specialty businesses. Quality and low cost and customization and low cost were assumed to he trade-offs. Tbis old competitive dictum was grounded in tbe seemingly well-substantiated notion that the two strategies required very different ways of managing, and, therefore, two distinct organizational forms. The mechanistic organization, so named because of tbe management emphasis on automating tasks and treating workers like machines, consists of a bureaucratic structure of functionally defined, highly compartmentalized jobs. Managers and industrial engineers study and define tasks, and workers execute them. Employees learn their jobs by following rigid rules under tight supervision. In contrast, tbe organic organization, so named because of its fluid and ever-changing nature, is characterized by an adaptable structure of loosely defined jobs. These are typically held by highly skilled craftsmen. They learn through apprenticeships and experience, are governed by personal or professional standards, and arc motivated by a desire to create a unique or breakthrough product. The mechanistic organization, whether in a manufacturing or a service setting, gives managers the control and predictability required to achieve high levels of efficiency. The organic organization yields the craftsmanship needed to pursue a differentiation or niche strategy. Each of tbese organizational forms bas innate limitations, however, which in tbe past have forced managers to choose one or the other. Almost all change is anathema to the mechanistic organization. And the artistry and informality#p#分页标题#e# at the heart of the organic organization defy efforts to regulate and control. The development of tbe continuous-improvement and tbe mass-customization models sbow that companies can overcome the traditional tradeoffs. In other words, companies can have it all. Continuous improvement has enahled thousands of companies to realize lower costs than traditional mass producers and still achieve the distinctive quality of craft producers. But mass customization has enabled its adherents, which are as varied as Motorola, Bell Atlantic, the diversified insurer United Services Automobile Association (USAA), TWA Getaway Vacations, and Hallmark, to go a step further. These companies are achieving low costs, high quality, and the ahility to make highly varied, often individually customized products. Is Your Company Ready for Mass Customization? Since achieving mass customization requires nothing less than a transformation of the husiness, managers must assess whether their companies must and wbetber in fact they can make tbe transformation. Not all markets are appropriate for mass customization. Customers of commodity products HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW September October 1993 111 MASS CUSTOMIZATION like oil, gas, and wheat, for example, do not demand differentiation. In other markets, like public utilities and government services, regulation often bars customization. In some markets, the possible variations in services or products simply are of little value to customers. Also, variety in and of itself is not necessarily customization, and it can be dangerously expensive. Some consumer electronics retailers and supermarkets today are experiencing a backlash from customers confused by too hroad a range of choiees. Continuous improvement will continue to be a very viable strategy for companies whose markets are relatively stable and predictable. But tbose companies whose markets are highly turbulent hecause of factors like changing customer needs, technological advances, and diminishing product life cycles are ripe for mass customization. To have even a chance of successfully becoming a mass customizer, though, eompanies must first achieve high levels of quality and skills and low cost. For this reason, it seems impossible for mass producers to make the leap without first going througb continuous improvement. Westpac, the Australian financial services giant, is a ease in point. It spent huge sums attempting to become a mass customizer hy automating both the creation and delivery of its products. It wanted to install software building blocks that would allow it to create new financial products like mortgages and securities more quickly. Strategically, the move#p#分页标题#e# made sense. Deregulation had spawned a dizzying Companies must break apart long-lasting, cross-functional teams and relationships and form dynamic networks. array of new products and services, and intensifying competition bad caused significant downward pressure on prices. Westpac tried to leapfrog continuous improvement by going from mass production directly to mass customization. Tbe challenges of automating inflexible processes, building on ossified products, and trying to create a fluid network within a hierarchical organization-particularly at a time wben the company was in poor financial condition due to intensifying competition in depressed marketsproved too difficult. Westpac has had to scale back significantly its ambitious dreams of becoming a tailored-product factory. As we bave stressed, even a company that has mastered continuous improvement must change radically the way it is run to become a successful Variety in and of itself is not customization-and it can be dangerously expensive. mass customizer. A company must break apart the long-lasting, cross-functional teams and strong relationships built up for continuous improvement to form dynamic networks. It must cbange the focus of employee learning from incremental process improvement to generating ever-increasing capabilities. And leaders must replace a vision of "being the best" in an industry with an ideology of satisfying whatever customers want, when they want it. Tbe traditional mechanistic organization, aimed at achieving low-cost mass production, is segmented into very narrow compartments, often called functional or vertical silos, each of which performs an isolated task. Information is passed up, and decisions are handed down. Compensation of employees, who are viewed as mere cogs in the wheel, is generally based on standardized, narrowly defined job levels or categories. In continuous-improvement organizations, tbe control system is much more, although never completely, horizontal. Inereasingly, teams have not only responsibility for but also authority over a problem or task area. Such organizations are moving to much more generalized and overlapping job descriptions as well as to team-based compensation. Wben mass customization is the objective, organizations structured around crossfunctional teams can create horizontal silos just as isolated and ultimately damaging to tbe long-term health of the organization as vertical silos have been. When Toyota expanded dramatically its variety, for example, it found that tightly linked teams did not share easily across their boundaries to improve the general capabilities of the company. As a#p#分页标题#e# result, the costs of increasing variety rapidly outstripped any value it was creating for customers. 114 HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW September-October 1993 To achieve successful mass customization, managers need first to turn their processes into modules. Second, they need to create an architecture for linking them that will permit them to integrate rapidly in the best combination or sequence required to tailor products or services. The coordination of the overall dynamic network is often centralized, while each module retains operational authority for its particular process. Job descriptions become increasingly hroad and may even disappear. And compensation for eacb module, wbether it's a team or an individual, is based on the uniqueness and value of the contrihutions it makes toward producing the product. Making Mass Customization Work The key to coordinating tbe process modules is a linkage system with four key attributes. 1. Instantaneous. Processes must be able to be linked together as quickly as possible. First, the product or service each customer wants must be defined rapidly, preferably in collaboration witb the customer. Mass customizers like Dell Computer, Hewlett-Packard, AT&T, and LSI Logic use special software that records customer desires and translates them into a design of the needed components. Then the design is quickly translated into a set of processes, which are integrated rapidly to create the product or service. 2. Costless. Beyond the initial investment required to create it, the linkage system must add as little as possible to tbe cost of making the product or service. Many service businesses bave databases tbat make availahle all the information they know about their customers and their requirements to all tbe modules, so nothing new needs to be regenerated. USAA, for example, uses image technology that can scan and electronically store paperwork and a companywide database, so every representative who comes into contact with a customer knows everything about him or her. 3. Seamless. An IBM executive once commented, correctly, "You always ship your organization." What be meant was, if you have seams in your organization, you are going to have seams in your product, such as programs that do not work well together in a computer system. Since a dynamic network is essentially constructing a new, instant team to deal with every customer interaction, the occasions for "showing the seams" are many indeed. The recent adoption of case workers or case managers is one way service companies like USAA and IBM Credit Corporation avoid this. These people are responsible for the company's relationship#p#分页标题#e# with the customer and for coordinating the creation of tbe customized product or service. They ensure that no seams appear. 4. Frictionless. Companies tbat are still predominantly continuous improvers may have the most trouble attaining this attribute. The need to create instant teams for every customer in a dynamic network leaves no time for the kind of extensive team building that goes on in continuous improvement organizations. The instant teams must be frictionless from the moment of their creation, so information and communications technologies are mandatory for achieving this attribute. These technologies are necessary to find the right people, to define and create boundaries for tbeir collective task, and to allow them to work togetber immediately without the benefit of ever having met. Using Technology. In mechanistic organizations, the primary use of technology is to automate tasks, replacing human labor witb mechanical or digital machines. People are sources of variation and are relatively costly, so mass producers often try to automate tbeir companies as much as possible. This has the natural effect of reducing the numbers and skills of tbe work force. In continuous-improvement eompanies, wbere workers are not only allowed but also encouraged to think about their jobs and how processes can he improved, technology is primarily used to augment workers' knowledge and skills. Measurement and analysis programs, computerized decision-support systems, videoconferencing, and even machine tools are aids, not people replacements. In the dynamic networks of mass customizers, technology still automates tasks where that makes sense. Certainly, technology must augment people's knowledge and skills, but the elements of mass customization require that technology must also automate the links between modules and en- Technology helps managers tap the capabilities of employees to service customers. sure that tbe people and tbe tools necessary to perform them are brought together instantly. Communication networks, shared databases that let everyone view the customer information simultaneously, computer-integrated manufacturing. HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW Septemher October 1993 115 MASS CUSTOMIZATION Understanding the Differences Mass Production The traditional mass-productian company is bureaucratic and hierarchical. Under close supervision, workers repeat narrowly defined, repetitious tosks. Result: low<ost, stondord goods and services. Continuous Improvement In continuous-improvement settings, empowered, cross-functional teams strive constantly to improve processes. Managers are#p#分页标题#e# coaches, cheering on communicotions and unceasing efforts to improve. Result: low-cost, high-quality, standard goods and services. workflow software, and tools like groupware (such as Lotus Notes) can automate the links so that a company can summon exactly the right resources to service a customer's unique desires and needs. Many managers still view tbe promises of advanced technologies through tbe lens of mass production. But for mass customizers, the promise of technology is not the lights-out factory or the fully automated back office. It is used as a tool to tap more effectively all the diverse capabilities of employees to service customers. While automating the links between modules is crucial, often some modules themselves can be automated by adopting, for example, a flexible manufacturing system that can choose instantly any product component within its wide envelope of variety. Motorola's Bravo pager factory in Boynton Beach, Florida, for example, can produce pagersthanks to hardware and software modularity - in lot sizes as small as one within hours of an order arriving from a customer. Tbe pager business is also a good example of how a mass eustomizer can automate links hetween modules. At Motorola, a sales rep and a customer design together, on a rep's laptop computer, the set of pagers (out of 29 million possihle comhinations) that exactly meets that customer's needs. Then tbe almost fully automated dynamic network takes over. The rep plugs the laptop into a phone and transmits one or more designs to the factory. Within minutes, a bar code is created with all the steps tbat a flexible manufacturing system needs to produce the pager. 116 DRAWINGS BY GARISON WEILAND Mass Customization Mass customization colls for flexibility and quick responsiveness. In an ever-changing environment, people, processes, units, and technology reconfigure to give customers exactly what they want. Managers coordinate independent, capoble individuals, and an efficient linkage system is crucial. Result: low-cost, high-quality, customized goods and services. As wonderful as these technological miracles sound, it is important to realize that technology is also potentially harmful. Mass customizers must periodically overhaul the linkages that tbey bave adopted because as the market, the nature of tbeir businesses, and tbe competition cbange, and as technology advances, any linkage system inevitably will become obsolete. Anotber caveat: in this age when automated systems are handling daily millions of customer orders and inquiries placed via phones or computer systems, mass customizers must constantly he on#p#分页标题#e# their guard against eliminating their opportunities to learn what their customers like or dislike. Companies must always make it possible for their customers to "drop out" of the automated system so tbey can talk to a real person who is committed to helping tbem. Learning from Failure. In the mechanistic organization, learning how to do something better is the prerogative of management and its collection of industrial engineers and supervisors. Workers only need to learn to do what is assigned to them; they don't have to think about it as well. The breakthrough of continuous improvement was tbe acknowledgment that workers' experience and knowhow can help managers solve production prohlems and contribute toward tightening variances and reducing errors. The differences hetween organizational learning in continuous-improvement and in mass-customization companies are most visible when you see I lARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW September-October 1993 117 MASS CUSTOMIZATION bow tbe two treat defects, Continuous-improvement organizations look at them as process failures, which tbe Japanese consider "treasures" because they provide the knowledge to fix problems and to ensure that failure never recurs. In the dynamic networks of mass-eustomization organizations, defects are considered capability ers witb the ability to capture valuable new knowledge. Motorola's and USAA's systems are good examples of this, as is Bally Engineered Structures Inc.'s (see tbe insert, "Overcoming the Hurdles at Bally"). This is very different from what goes on in both mass-production and continuous-improvement organizations. Typically, in those settings, there are almost no individual cus- •|- . » ^ I tomer interactions that generate It IS heresy to try to know what to new knowledge. produce in the future. Customer orders will determine that. failures: the inability to satisfy the needs of some specific customer or market. Tbey are still valuable treasures; but rather than sparking a spate of process- improvement activities, these defects call on the organization to renew itself hy enhancing the flexihility within its processes, joining with anotber organization tbat has the needed capability, or even creating completely new process capabilities - whatever it takes to ensure tbat tbe customer is satisfied and, tberefore, tbat capability failure doesn't happen again. Capturing customer feetlhack on capability failures is crucial to sustaining any advantage that mass customization yields. A company that does this well is USAA, which targets its financial services and consumer goods to events in a customer's life, such as huying a house or car, getting married,#p#分页标题#e# or having a baby. Its information system allows sales reps to get customer feedback quickly on the phone and route it instantly to the appropriate department for analysis and action. At Computer Products, inc., a manufacturer of power supplies, marketing managers and engineers cold-call customers every day not to make a sale hut to understand their prohlems and needs and to discuss product ideas. They then enter tbe information into a database that serves as an invaluable reference throughout the product-development cycle. Applied Digital Data Systems, a unit of AT&.T's NCR suhsidiary, uses a database system to store all its production information, including workers' comments and suggestions, and tben regularly analyzes it to improve hoth its processes and products. The capahility to codesign and even coproduce products with customers provides mass customiz- Creating a Vision. In addition to different attitudes ahout customer interactions, leaders of continuousimprovement companies and mass customizers foster very different approaches to the future. The former think they know wbat the organization needs to do to succeed in the future, whereas the latter helieve that it's impossible to know and heresy to try hecause the future should he shaped hy each successive customer order. Leaders of continuous-improvement organizations provide a vision of not just what is to he done today hut also what needs to he realized tomorrow, and this can work, provided that the market is relatively stahle. Their vision is often expressed in terms of some competitive ideal of customer satisfaction. Allstate's "To he the hest," Federal Express's "Never let tbe best get in the way of better," and Steelcase's "To provide the world's hest office environment products, services, systems, and intelligence" are good examples. Tbe common vision provides everyone in the company with the motivation, direction, and control necessary to continue USAA sales reps get customer feedback quickly on the phone and route it instantly to appropriate departments. improving all the time. Without a sustained vision, a company's attempts at process improvement can hecome lost in "program-of-the-month" fads or lip service to quality. The highly turhulent marketplace of the mass customizer, with its ever-cbanging demand for innovation and tailored products and services, doesn't result in a clear, shared vision of tbat market. A standard product or market vision isn't just insufficient; it simply doesn't make sense. In 118 HARVARD BUSINESS KEVIEW September-October 1993 a true mass-customization environment, no one#p#分页标题#e# knows exactly what the next customer will want, and, therefore, no one knows exactly what product the company will he creating next. No one knows what market-opportunity windows will open, and, therefore, no one can create a long-term vision of certain produets to service those markets. But everyone does know that the next customer will want something and the next market opportunity is out tbere somewhere. Many companies are articulating this scenario by using words like "anything," "anywhere," and"anytime." Peter Kann, chief executive of Dow Jones, describes his organization's strategic goal asproviding "husiness and financial news and information however, wherever, and whenever customers want to receive it." Nissan's vision for theyear 2000 is the "Five A's": any volume, anytime,anyhody, anywhere, and anything. Motorola's pager group has a TV ad that asks, "How do you useyour Motorola pager?" Various people answer withphrases like, "Anytime," "For anything," and"Anywhere I want." No matter what they are called, such ideologiessay two things ahout an organization: one, we don'tknow exactly what we'll have to provide to whom,and two, within our growing envelope of capabilities, we do know that we have or can acquire the capahilitiesto give customers what they want. 留学生论文网Leaders who can articulate such an ideology and create the dynamic network that can make it bappenwill succeed in moving tbeir organizations far beyond continuous improvement to the new competitivearena of mass customization. Authors' note: IBM Consulting Group partners and consultantscontributed significantly to the development ofthe ideas in thisarticle. The research was sponsored in part by the IBM Consulting Group and the IBM Advanced Business Institute. Reprint 93509  CARTOON BY NICK DOWNES 119 |